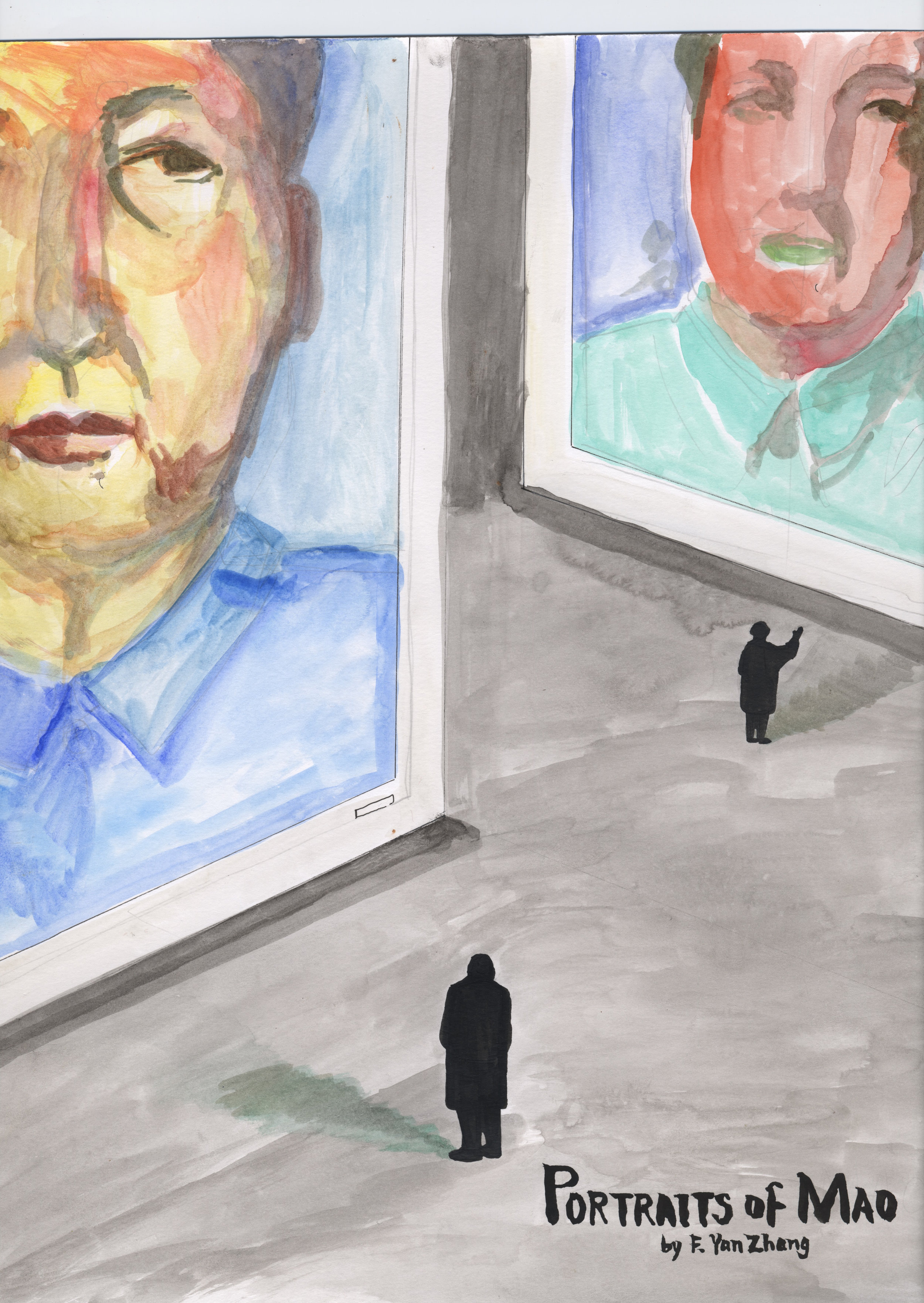

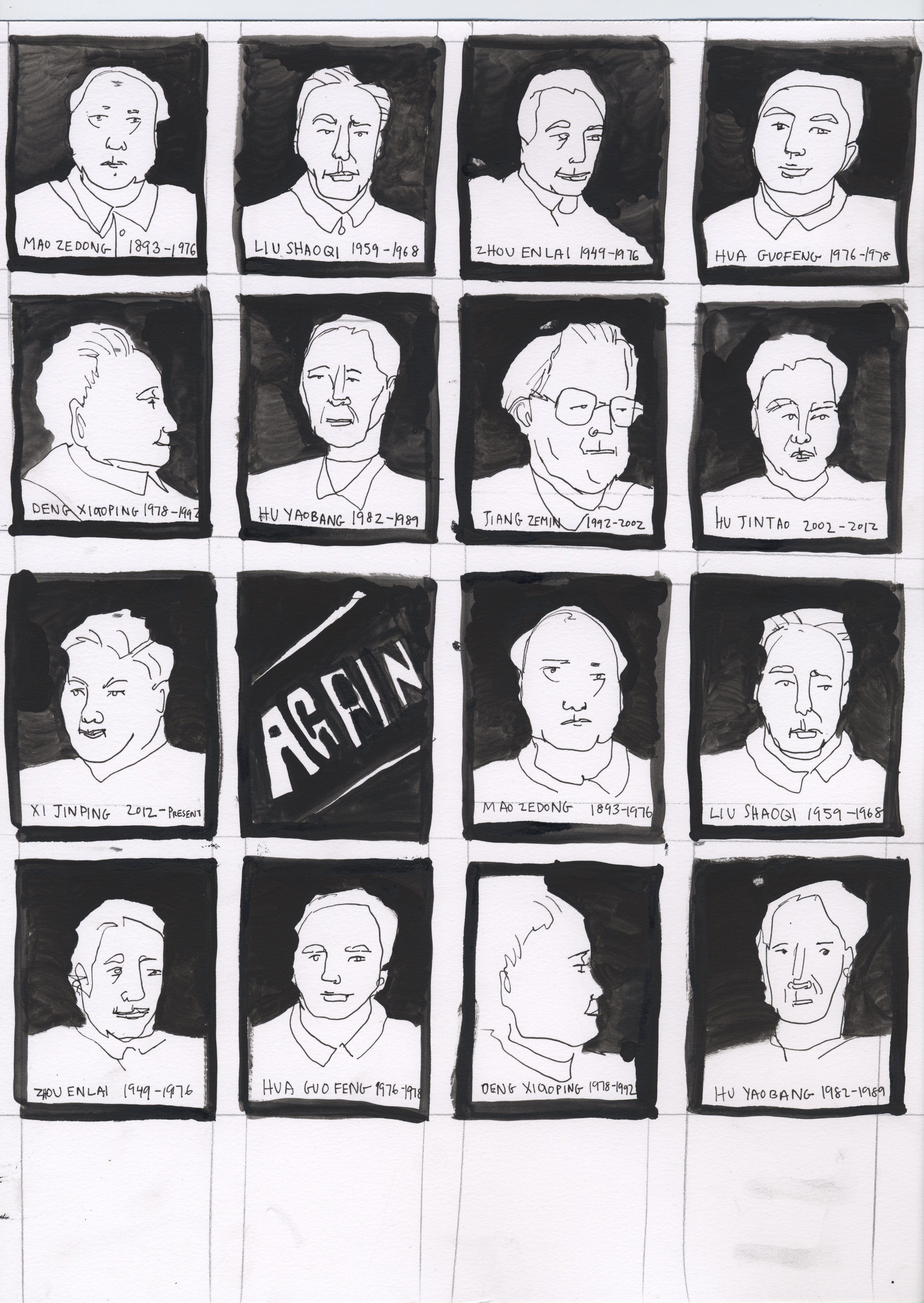

Portraits of Mao

Cryogenic

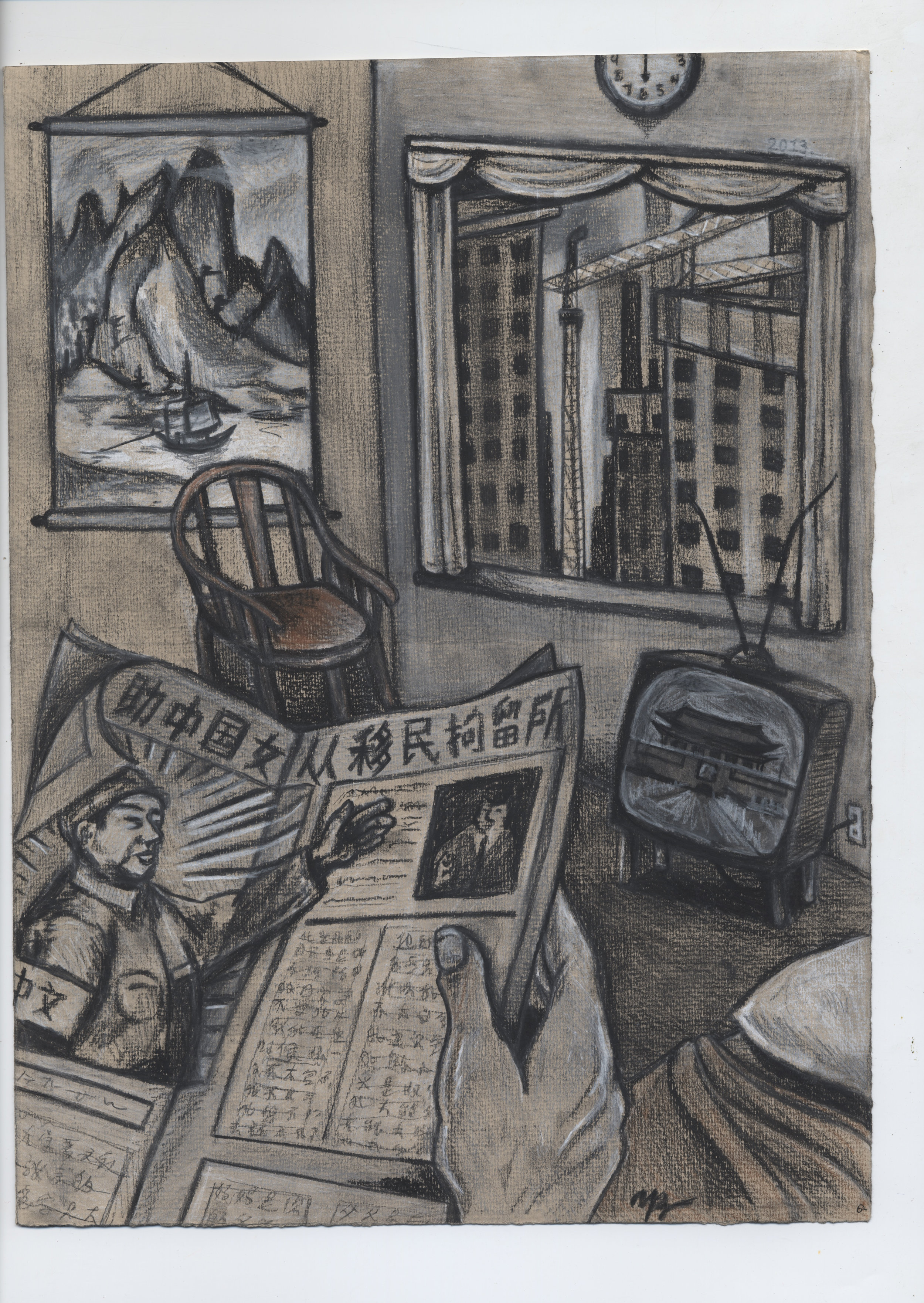

There is a building somewhere in the bowels of Beijing, beneath the gimlet sky and jungle streets. It is probably not too far from Tiananmen Square, where thousands of tourists scurry under the eyes of pimpled plainclothes policemen. On even the smoggiest of Beijing days, the air inside remains cool and dry. There are probably no windows and no indication of this building’s meaning or purpose.

This building holds national treasures of the People’s Republic of China, of no monetary value, yet zealously guarded: over 50 years’ worth of 15 by 20 foot canvases, all painted over in white. Each one-and-a-half-ton canvas was carted here in the dead of night, a monumental secret. To destroy one is a criminal act. If you were to scrape away the paint, a damaged but recognizable image would emerge: the face of Chairman Mao Zedong.

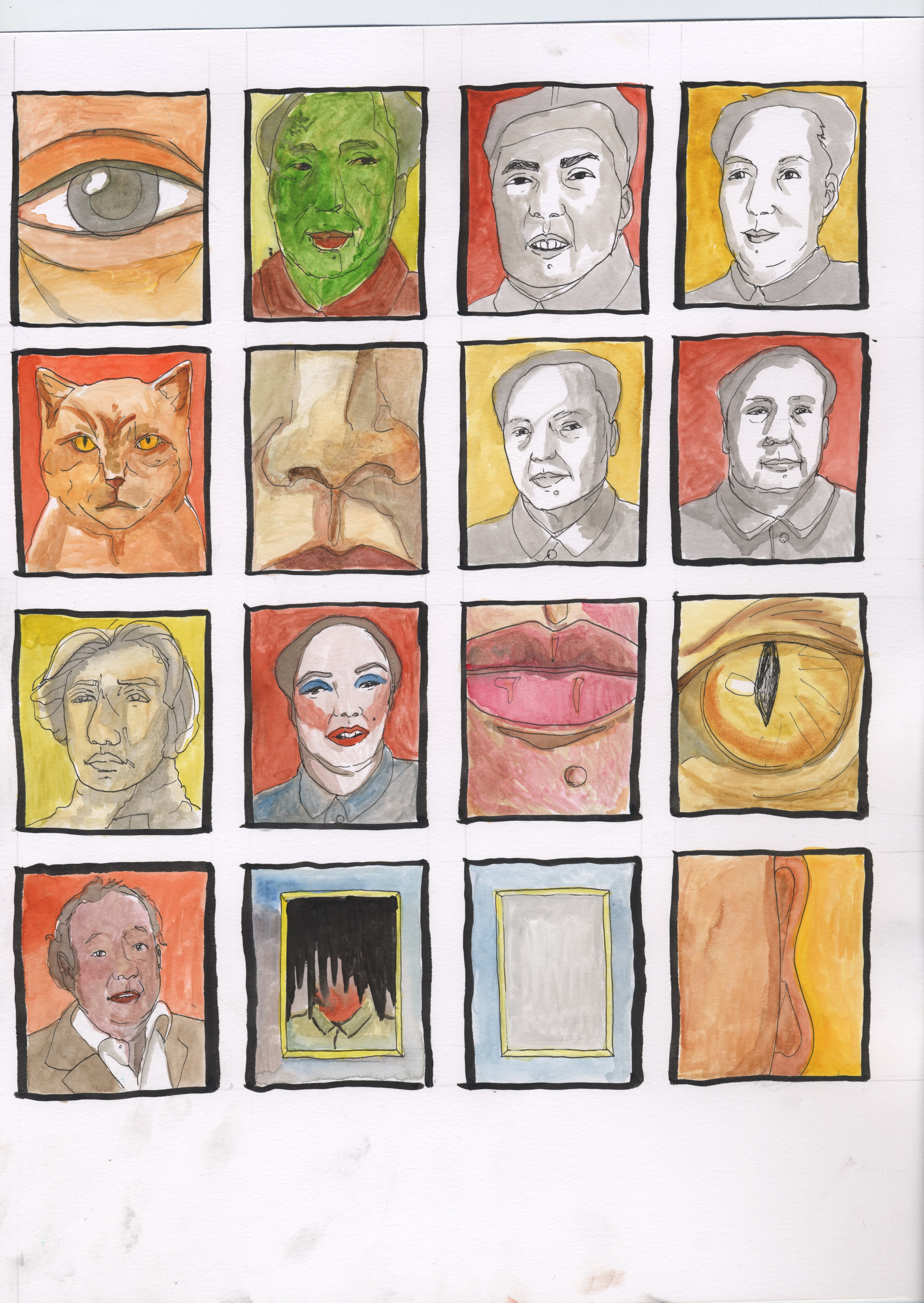

Like a game of spot-the-difference, each portrait would seem identical—receding hair, plump cheeks, mole on the chin—save for some slight detail. In some, Mao’s face would look stern and fatherly, as if disciplining an errant child. Recent portraits would present a flushed, benevolent Mao with a Mona Lisa smile. The earliest portraits would have him donning an octagonal cap and coarse woolen jacket.

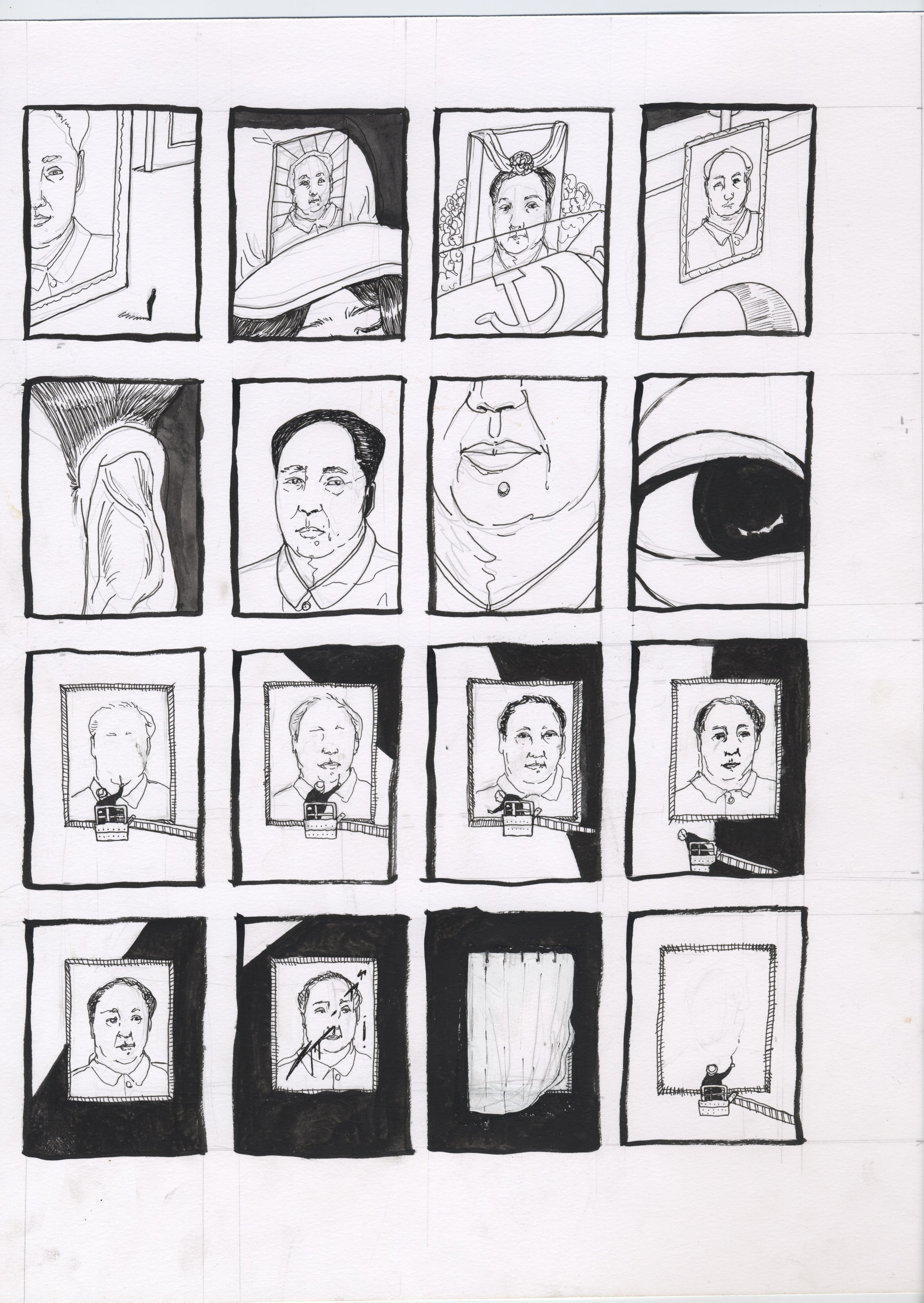

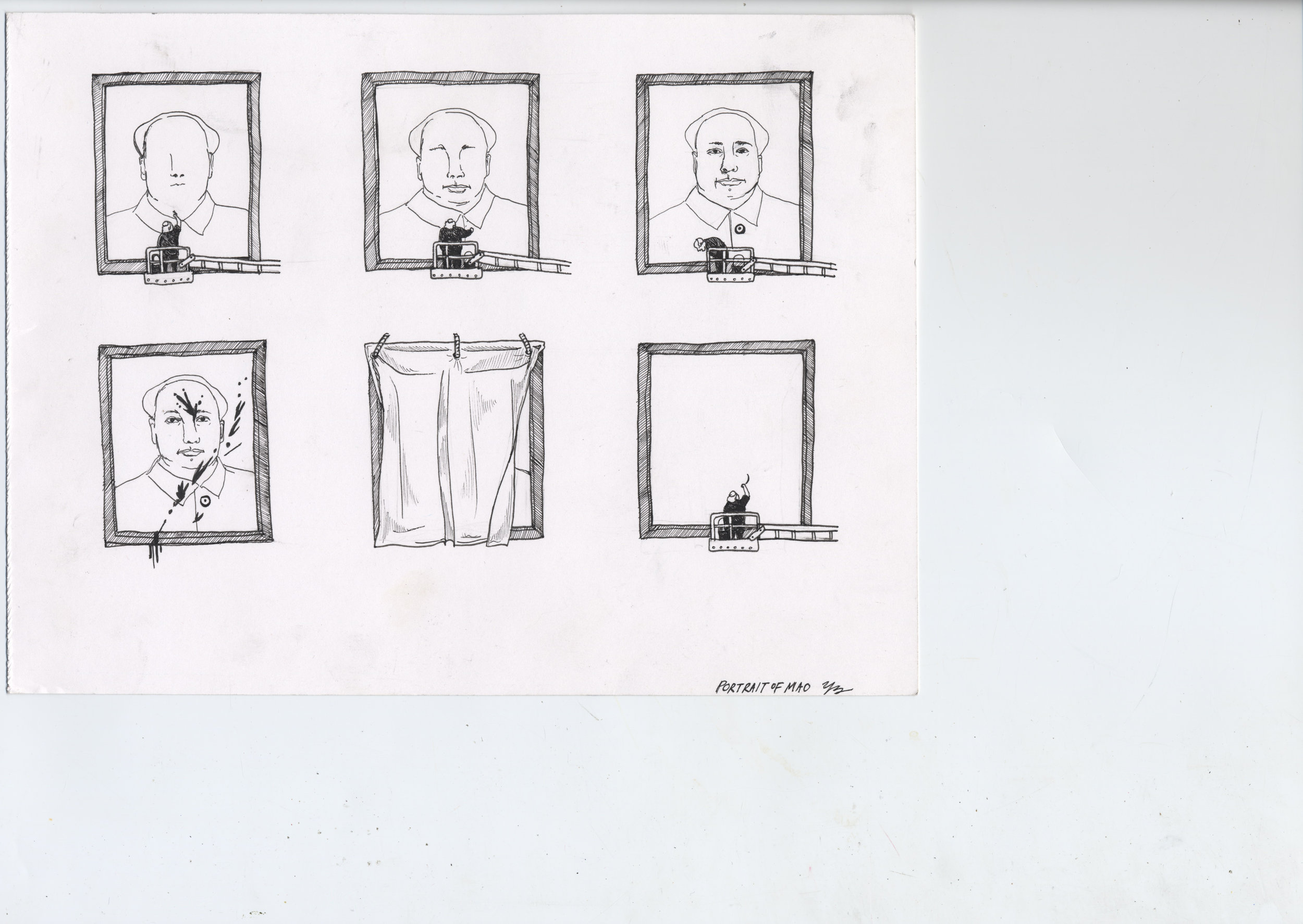

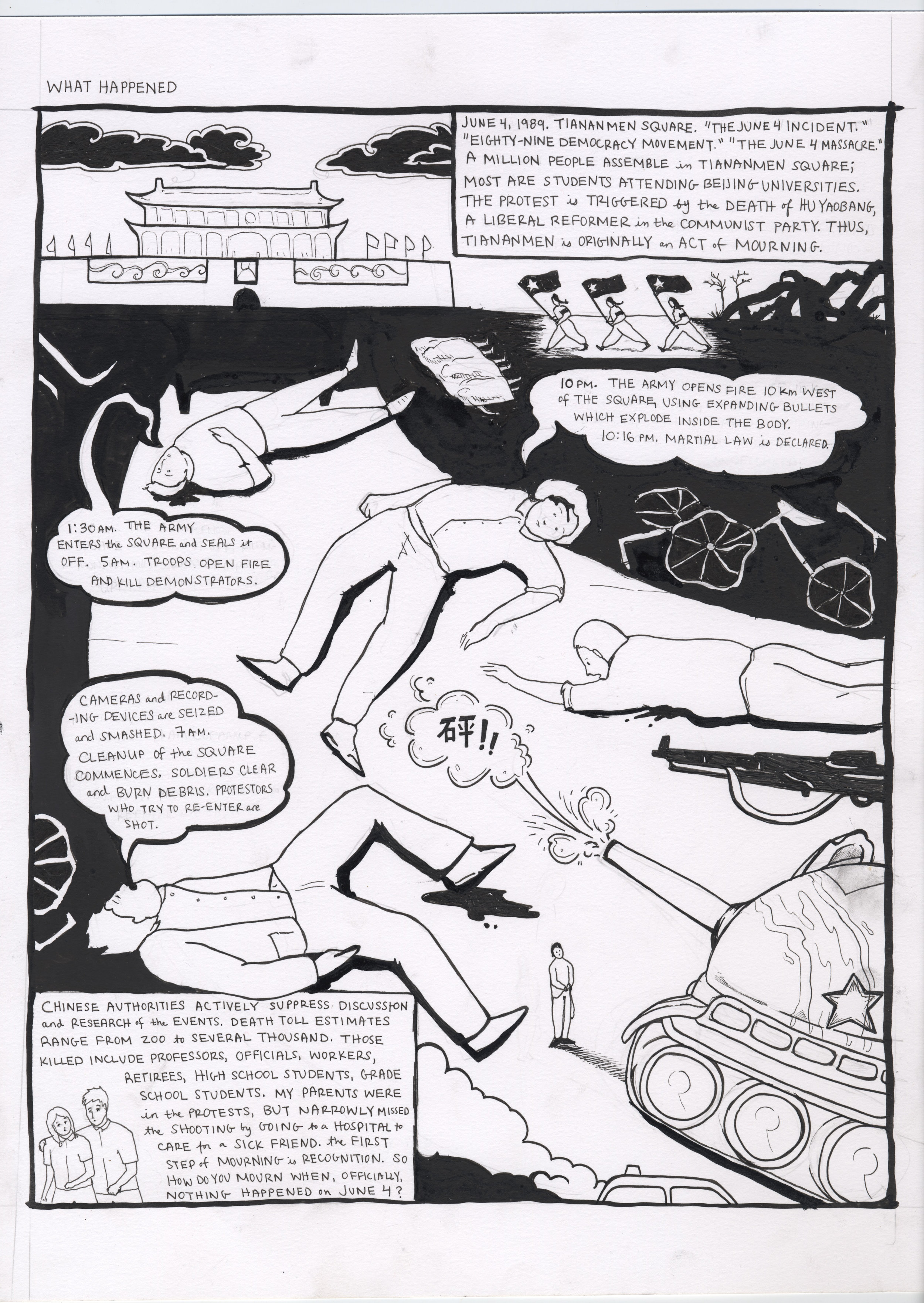

All the portraits share one certainty. Starting from the first in 1950, each has hung for one year, more or less, over the gate to Tiananmen Square in Beijing. A small handful have been assaulted by rotten fruit, black paint, and even fire. During the Tiananmen Square protests of 1984, one was pelted with three ink-filled chicken eggs. Whether it survives its year-long tenure or not, each canvas comes to the same end. It is taken down, painted over in white, and placed in storage for an imagined future, when the country might need it again.

Lifework

If the storage building is a graveyard—a cryogenic vault—then another building tucked away in a corner of the Forbidden City is a birthplace. It is called “the metal shack” by those in the know. Built in the early 1970s, the shack is fireproof and would be air-proof if not for the vents near the door. Despite its utilitarian appearance, the metal shack is an art studio.

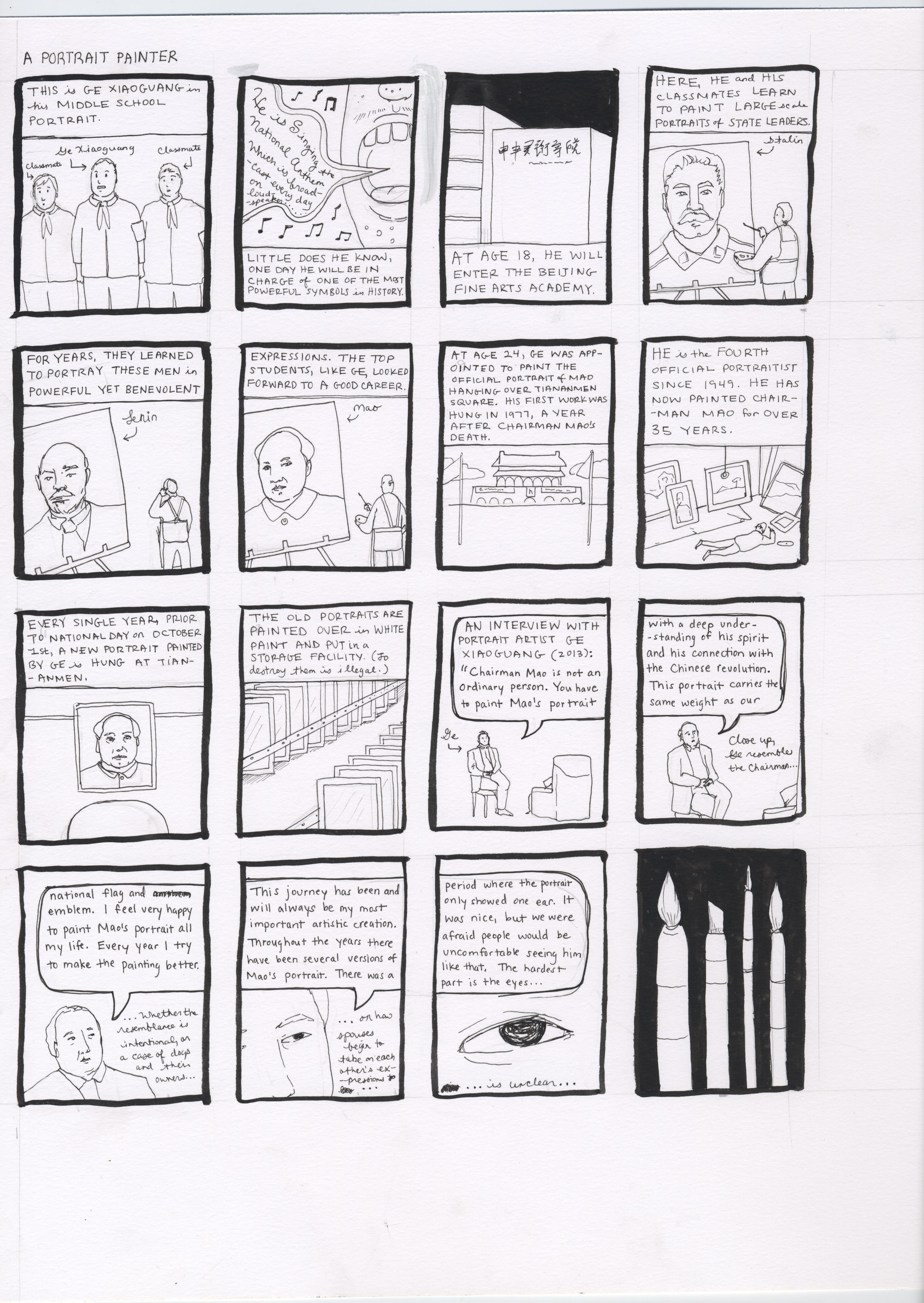

Here, Ge Xiaoguang has worked since 1976. According to rumor, the government pays Ge a salary of 250 dollars every month to lead a team of artists who paint China’s political leaders, from past heroes to modern luminaries. His main and most important job is duplicating the Tiananmen portrait of Chairman Mao, so that it may be replaced every September. Ge boasts that his nearly 40 years of practice allow him to complete the portrait in only 50 days.

“It is still hard to get him right, because it is more than just another piece of art,” he says. “Every year I try to make the painting better. This has been and will always be my most important creation.”

The official No. 4 Standard Photograph of Mao Zedong, owned by the state-operated New China News Agency, is Ge’s blueprint. He makes a few modifications. The official photograph is monochrome, so Ge remakes Mao in ruddy technicolor, aglow with a hearty red blush.

Ge analyzes the portrait’s pose meticulously. If Chairman Mao were to face straight forward, the portrait would lack dynamism and depth. So Ge turns Mao’s face slightly to the side. Not too far, however, for both ears must always remain visible. One of Ge’s predecessors was banished to a rural district to work as a carpenter, his punishment for painting only one visible ear. Authorities thought the arrangement might imply that the Chairman was but halfhearted in his attention to the voice of the people.

Nor were their fears entirely unfounded. Reports circulated of a visiting schoolboy, who pointed at the Tiananmen portrait and shouted, “Look! Chairman Mao has no ear!”

Some days, Ge ventures forth from the metal shack and into Tiananmen Square. He stands on a scaffold and works directly on the currently displayed portrait. Its giant size makes it impossible to take in at a close quarters, constantly compelling him to descend from the scaffold to view it from a hundred feet away. While he perches on the scaffold, Ge sweeps the painting with a fan brush to produce an airbrushed quality. Mao’s face glows jovially through the canvas.

Workshop

Ge was once a protégé. Now he’s the only one of his kind. Once, dozens of Beijing art students studied the art of Mao portraiture. His image was in constant demand. It hung in schools, workplaces, and factories. It was pasted onto banners, buttons, and badges.

From the years 1964–1976, Wang Guodong—a recluse who gave no interviews, and of whom no public photographs exist—was the only official painter of Chairman Mao. In his youth, Wang had been the errant painter who gave Mao only one ear. Banished by the Red Guard to a remote framing factory, he was forced to construct picture frames. But after two years in exile, Wang reclaimed his official title and kept it for two more decades.

In 1975 government authorities, perhaps anticipating Wang’s approaching old age, demanded that he take on apprentices. Wang selected ten Beijing art students—including a 21-year-old Ge Xiaoguang—more for their political reliability than their artistic talent. From the moment of their selection onward, they studied only political portraiture: Marx, Engels, Lenin, Stalin, and most of all, Mao. Even with such bounds on their creativity, disparities in talent emerged. Some, like Ge, excelled. Others, it seemed, would never be able to capture Mao’s spirit. Their color palette was too yellow and sickly or their brushstrokes too crude.

Despite the apprentices’ varying levels of aptitude, orders poured in from all over the country. Factory-style, the apprentices painted non-stop. Their sentiment was not creative. They viewed themselves as art workers, rather than artists. Like interchangeable parts, not a single portrait from Wang’s factory was ever signed with a name.

By the 1980s, as China entered its great economic revolution, the demand for Mao’s image had waned. Bicycles gave way to cars, caps gave way to blue jeans, little red books were cast aside for chat rooms. Mao’s face fell out of fashion as brand name logos became de rigueur.

Excepting Ge Xiaoguang, Wang’s apprentices turned elsewhere. The hand-drawn boldness of their propaganda style translated well to the world of advertising. Instead of replicating Mao, they drew movie posters, cosmetics labels, commercials, magazines.

By the time Mao portraits had become passé, Wang Guodong had already retired. He relinquished his brush in 1976, the year of Mao Zedong’s death, for the first time (even through his years at the framing factory, Wang had gone on painting). In 1976, for the first and only time in history, a black-and-white photograph replaced the technicolored portrait over Tiananmen, in an expression of mourning.

Chopping Block

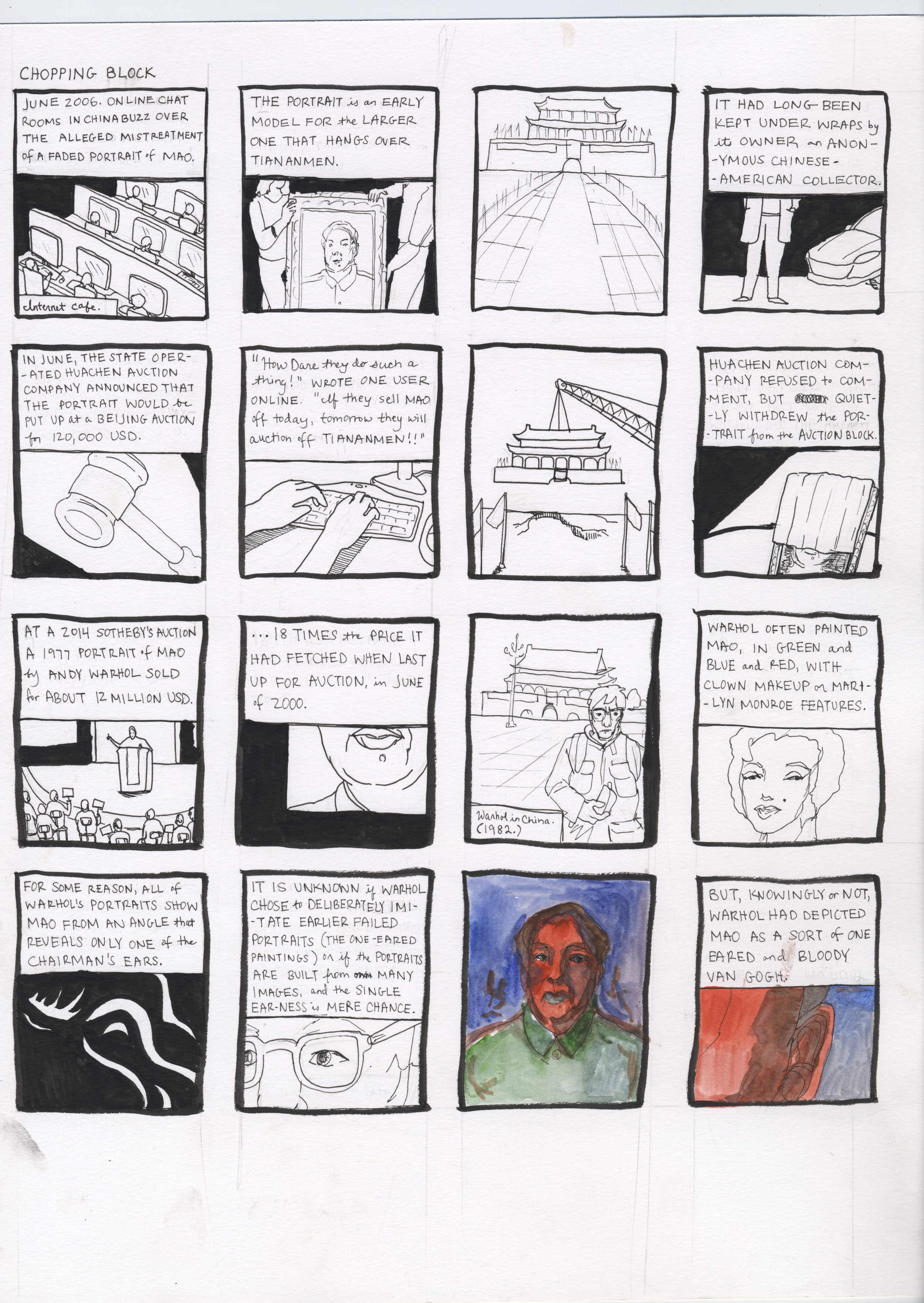

In June 2006, online chat rooms across China exploded over the alleged mistreatment of a faded, gray, gilt-framed 1950 portrait of Mao. The painting, an early model for the larger one in Tiananmen, had long been kept under wraps by its owner, an anonymous Chinese-American collector. In June, the state-controlled Huachen Auction Company announced the painting would go up at a Beijing auction for an estimated 120,000 dollars.

“How dare they do such a thing,” wrote one user online. “If they sold Mao’s portrait today, they will auction off Tiananmen Square tomorrow!” Huachen Auction Company refused to comment, but quietly withdrew the portrait.

At a 2014 Sotheby’s auction, a 1977 portrait of Mao by Andy Warhol sold for about 12 million dollars—18 times the price it fetched when it was last up for auction in June 2000. The painting shows Mao with a yellow sun-halo over his face, casting his eyes and left side in a deep, inky shadow. His jacket is glossed in crimson.

Warhol often painted Mao: in green and blue and red, with clown makeup, or Marilyn Monroe-style. For some reason, all of Warhol’s portraits show Mao from an angle that reveals only one ear. It is unknown whether Warhol chose to imitate Wang Guodong’s failed portrait, or if Warhol fabricated his own portrait of Mao from existing images. Knowingly or not, he had depicted the Chairman as a bloody one-eared Van Gogh.

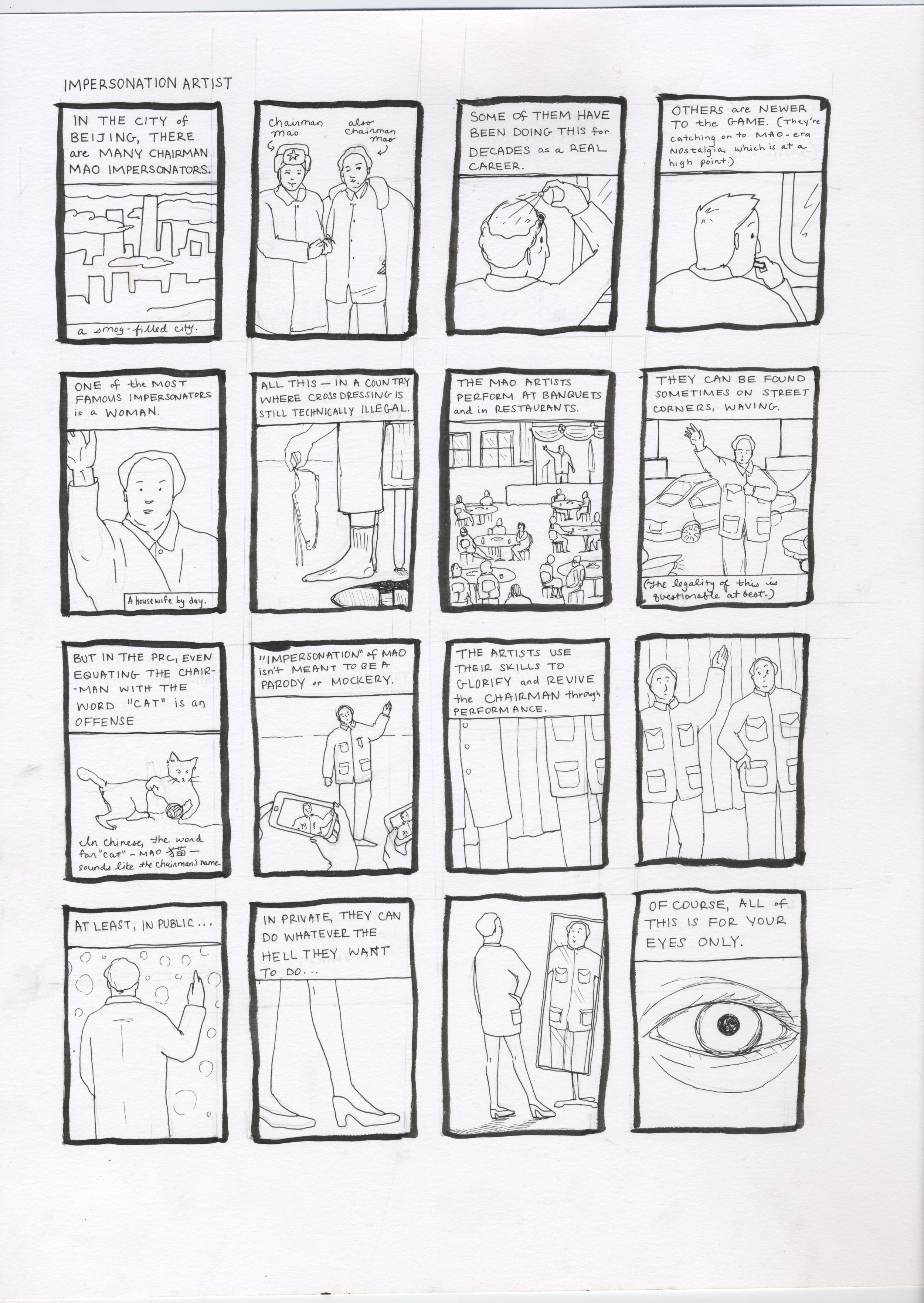

Novelty

Warhol’s repetitions of Mao are far outstripped by those of Ge Xiaoguang’s former peers. In an age of computer-manufactured graphics, these political art workers’ hand-drawn skills are out of fashion yet again. So they’ve returned to their roots, creating novelty items and nostalgic propaganda. Iterations of Mao now appear on bookmarks, posters, pins, playing cards, and liquor bottles.

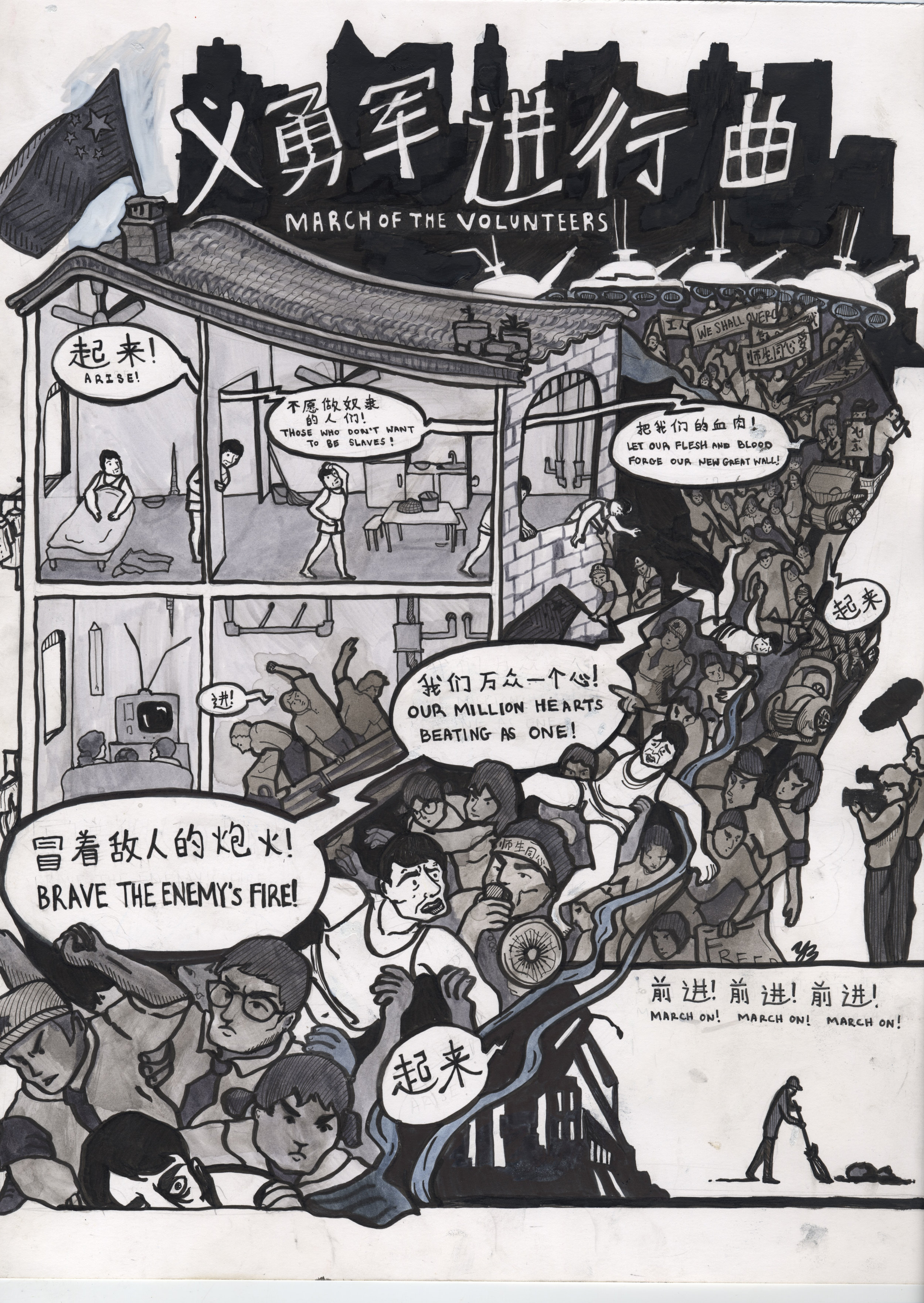

A restaurant on the outskirts of Beijing called The East is Red goes a step further, repackaging the Cultural Revolution as a dinner theater. Giant black-and-red socialist-realist murals and stenciled portraits of Mao cover the restaurant’s walls. Waiters dressed in Red Guard costumes scamper between tables, while entertainers toting plastic rifles serenade customers with revolutionary songs like “March of the Revolutionary Youth” and “I Love Tiananmen.”

Wedding parties, birthdays, and reunions crowd the massive concrete atrium. Old ladies stand and wave miniature red flags, tears in their eyes. Banquet tables groan under the weight of dishes with translated English titles like “a peasant family is happy” (root vegetables and steamed bread), “recalls past suffering the food” (grain with sand or hard millet), and a speciality from Mao’s home province, “Hunan earth, Hunan passion” (corn cakes stuffed with wild nettle greens).

Younger customers, a generation removed from the Revolution, view the restaurant as an entertainment, akin to a Tudor-themed bar in England. “People in my generation barely ever hear or read anything about the Cultural Revolution, so restaurants like this are really fun for us,” says a young patron. “Today’s China feels so cold and detached compared to the land my grandparents lived in.”

For older customers, verdicts are mixed. “The first time I came here,” one says, “I was frightened. Sometimes, when everyone was singing, I felt like maybe the bad times were coming back. Maybe this could happen again. But then some songs made me so happy, too.” The performers onstage belt out rousing verses, “One after another following the party, smashing the evil of the old world! The East is red, the sun is rising, China has birthed a Mao Zedong.”

As restaurants dish out Mao-era specialities, Mao’s original portraitists and newcomers continue to churn out images for companies with nostalgic names like Red Years (a playing card manufacturer) and Red Star (a hard liquor brand). On city streets, Mao impersonators of varying levels of believability (some are women) pose for photos with tourists, like the costumed superheroes of Times Square.

Posterity

It is unknown whether Ge Xiaoguang will retire, whether he has selected an apprentice to succeed him, or whether he is even the real painter behind the Tiananmen Square portraits. Ge may simply be a photogenic face authorities have chosen to represent the artist, when the “real painter” is really an assemblage of dozens of interchangeable art workers.

But Ge does look right when placed next to Mao’s portrait. If he is the artist, then his years of work have transformed him into a convincing double of his subject, save for the lack of a trademark mole on the chin. Ge’s receding hairline follows the same pattern, his round cheeks glow with the same jovial flush, his eyes, ears, nose, and mouth possess something of the portrait’s keen benevolence.

Of previous official portraitists, little is left but a handful of faceless names: Zhou Lingzhao, Zhang Zhenshi, Wang Guodong. Unlike them, Ge Xiaoguang has become something of a minor Beijing celebrity. Walking the streets near Tiananmen, he is often recognized by passersby. The painter and the portrait have converged.

A picture exists of the painter that shows him standing on his scaffold, facing the Mao portrait with his back turned to the photographer. It’s a closeup shot, and all we can see of Mao are his eyes. At close quarters, they look bittersweet. Between them stands the artist—half turned, head tilted, lifting his brush to add one more stroke.